Lewiston, Maine tragedy sparks wider support for ASL interpretation

THIS ARTICLE BY KAYLA BERKEY APPEARED IN THE NATIONAL “NEWS FROM AROUND THE WORLD” PRODUCED BY THE UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST

by Kayla Berkey | published on Dec 19, 2023

This holiday season will be the first for many still grieving since the Oct. 25 shooting in Lewiston, Maine, where 18 people were killed and 13 injured.

One of the tragedy’s impacts has been widening awareness of the need to make community information and mourning rituals accessible in American Sign Language. Four of those who died when a gunman opened fire at Schemengees Bar & Grille were deaf, causing significant impact on Maine’s Deaf community and their loves ones.

It’s a need that Marisa Zastrow — a certified ASL interpreter in the state and a member of Cumberland Congregational Church in Cumberland, Maine — has been dedicated to meet. Joshua Seal, her colleague and good friend, was one of the four deaf people who died.

“It’s been a really, really hard time,” Zastrow said. “As interpreters, we hold the stories of our clients and of our community. It’s a very small deaf community in Maine, but an incredible community. We were there for births and weddings, high school graduations and sticky parent-teacher conferences and doctor’s appointments — it’s that same interpreter who, in my perspective, is invited into the lives of a deaf person at different moments in their journeys and their stories.”

In the wake of this crisis, the Lewiston Deaf Access Fund arose in early November. As a joint effort of the Massachusetts Council of Churches and the Maine Council of Churches, it aims to build funds to provide accessible rituals of worship and grieving, which includes compensating ASL interpreters for funerals of those killed in Lewiston.

Language access in fearful times

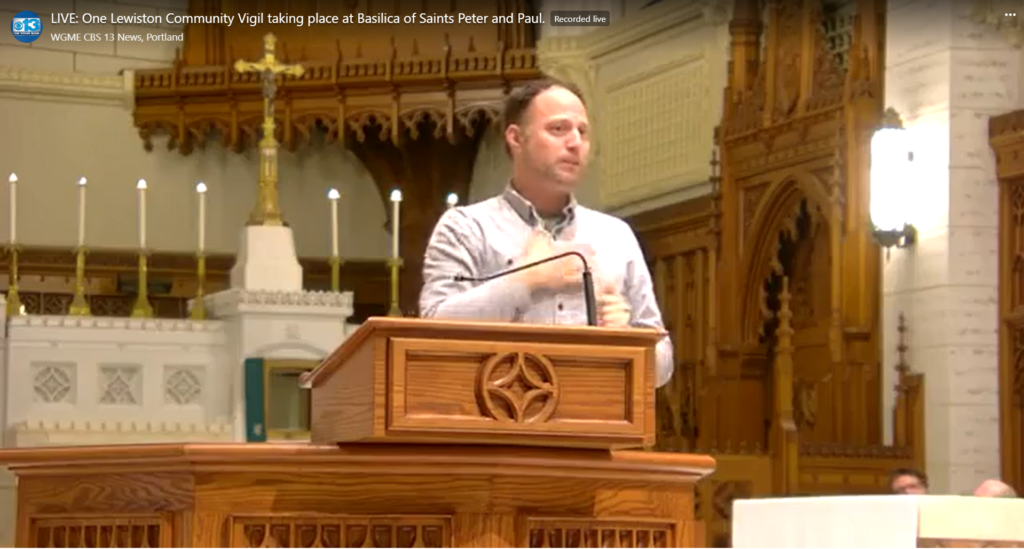

Following the shooting in October, ASL interpreters jumped into action to make TV news briefings accessible during fear and confusion in the ensuing two-day manhunt. Following complaints from deaf viewers that the interpreter was not consistently visible on broadcasts, state officials opened an Oct. 27 press briefing with directives that the interpreter be included in all camera frames for language access.

It was especially difficult in the wake of the shooting for victims’ families and survivors who “were denied to have in-person interpreters and were forced to use unreliable Video Relay interpreters which kept disconnecting, and/or they were in so much pain that it was difficult for them to focus on the screen,” according to Kevin Bohlin, a member of the Deaf community who provides training in Deaf culture and ASL for families with Deaf/Hard of Hearing babies and leads an ASL interpreting department.

Bohlin noted the unique value offered by in-person interpreters: they can better establish connection, move around to adjust to access needs and convey information in the Deaf community’s native language.

“Our community had to work hard to ensure that those needs were met instead of grieving with the general community,” he said.

Access needs remained crucial as community gatherings, funerals and memorial services were held for those who lost lives throughout November. While victims’ assistance funds helped to cover funeral costs, they did not adequately cover the cost of interpreters.

“Funding was always an issue as nobody knew who was responsible to pay for interpreter services,” Bohlin said. “This placed the burden on the Deaf community to actively find money for access.”

Telling stories for healing

While interpreters traveled from surrounding states to offer support, Zastrow said that they quickly heard requests from the Deaf community for the small pool of local interpreters, like herself, who had been present at their life events and early responders following the shooting.

“We stopped asking who’s paying for it very quickly, because being together and being community and retelling their story has been such a huge piece to the healing for deaf people, who couldn’t hear that night and did not have the whole story,” Zastrow said. “It’s been a lot of pro bono work, and we recognize, after three weeks, the financial impact is huge to the interpreters who have been called in repeatedly.”

Some of the funerals needed up to five interpreters to provide interpretation for the service, as well as times of socialization and sharing memories for spouses, family members and survivors.

There were nine men gathered at Schemengees for a cornhole tournament at the time of the shooting — a longstanding weekly gathering that many of them had participated in for years. Because the cornhole tradition had created connections even across language barriers, it made ASL accessibility a priority at many of the funerals.

Quick response to accessibility needs

These needs inspired the creation of the Lewiston Deaf Access Fund to ensure that access was readily available and that interpreters — who were also grieving — received compensation for their work.

The fund came together when the Rev. Laura Everett, executive director for the Massachusetts Council of Churches and a United Church of Christ minister, connected with Zastrow and learned of the unmet need for a common fund to receive contributions for ASL interpreters.

Everett realized that while the Rev. Jane Field, executive director for the Maine Council of Churches, was engaged in responding to their community’s grief, the Massachusetts Council could step in and offer administrative support to establish the fund. Through an abundance of collaborations, they were able to create the Lewiston Deaf Access Fund within about a day of learning of the need, according to Everett.

“I think the promise of the Gospel for me is not that we won’t suffer, but that we won’t suffer alone,” she said. “Marisa’s witness that we are accompanying is so profound, and to be able to participate in some small way — I’m so proud of this … We’re seeing gifts from people who aren’t religious or Christian but believe that mourning well matters and want to participate. This is church at its best, that we can notice a need and meet it, and that there’s a Gospel commitment that there’s enough for all when we share. I’m profoundly grateful that we can do that in a time of incredible sadness.”

She noted the special importance of responding in this instance when a minoritized community has been disproportionately affected.

“We believe that all should be able to gather and mourn, and there is a significant barrier to full access. There’s an unmet need here, and we think we’ve got a way, quickly, to be able to meet that need,” she said. “This is a testimony to what a more full inclusion can look like.”

Field describes the state of Maine as “a small town with really long streets where everyone knows everyone,” emphasizing the widespread impact of the shooting.

“Trauma is horrific enough, and I’ve been working with clergy in the greater Lewiston area — about 18 churches that have been impacted are under our umbrella,” she said. “Most or all of them are part of the hearing community, and they have been horrifically traumatized, but imagine on top of that not having access to information, to ritual, to the stories that are circulating. In times of crisis like this, sometimes it’s telling the story over and over again where healing starts. To be shut out from that because of a lack of accessibility to interpreters is unthinkable and intolerable.”

‘Here for the long haul’

While the funerals have taken place, there remains ongoing need for supporting the Maine Deaf community. The Access Fund will be housed with the Maine Association for the Deaf, and distributions will be made through Disability Rights Maine.

“Deaf is an invisible disability, and our needs for access are easily overlooked … The mainstream society can look at a Deaf individual and not know that they are deaf unless they are using an assistive hearing device. The community is truly missing out on information without interpreters, closed captions or even advanced communication,” Bohlin said. “Through this experience where the Deaf community was directly impacted by gun violence that happens on a daily basis, we have lost four beloved members of the community and five members have been traumatized/injured. Our eyes have truly opened about how we can improve access on a variety of levels.”

https://www.facebook.com/plugins/post.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2FMainePublic%2Fposts%2Fpfbid072raP62HSjSkcBRL4iVosUs6H7LRP2sXyoq6bRTCshjZLsVbjz6KpFHzFpExJezCl&show_text=true&width=500

“This isn’t going to go away by Christmas,” Field said. “The ripples from this will go out not only in people affected, but through time, and the church will be here for the long haul. After the TV cameras have gone, and after the newspaper articles go onto the next thing, we’ll still be here. And so will those organizations that do extraordinary work in the state — Maine Association for the Deaf and Disability Rights Maine.”

Zastrow said this fund will help at future events that wouldn’t typically have an ASL interpreter but should, like marches advocating for safer gun laws or Pride events. She said that the wives of those who died have also expressed interest in getting together to share their stories.

Donations in support of language access can empower the Deaf and Deaf-Blind communities “by breaking down barriers and promoting equal participation in various aspects of life,” Bohlin said. “We are truly grateful for the Congregational Church/United Church of Christ being proactive and collecting funds to support access for our community — the donations will benefit the Deaf/Deaf-Blind community in the long run.”

He pointed out that, in the late 1800s, the Congregational Church helped launch the Maine Association of the Deaf.

“Without the support, Maine Association of the Deaf may never have happened,” he added. “We look at this as a full circle of communities supporting each other.”

People can still donate funds to the cause.

“I know it doesn’t solve everything. I know it doesn’t even solve most things,” Everett reflected in a letter to her council’s board. “Marisa and her colleagues [had] 11 funerals … which is far too much for any community to endure. But I want you to know of this small and necessary good, even here.

“As you are able and led, share and rejoice. Even here. Even now. While we are at the grave, we make our song.”

Content on ucc.org is copyrighted by the National Setting of the United Church of Christ and may be only shared according to the guidelines outlined here.