Saints of the Season

Advent has begun again—that season of expectation when we anticipate the arrival of “God-with-skin-on,” the Christ child lying in a manger, asleep on the hay. Everything is about the big countdown—in church, we count the weeks: 1st week of Advent, 2nd week, 3rd, 4th. Out there, we count the shopping days left until Christmas. We think of this waiting period as a happy time, full of joyful preparations and building excitement. But the scripture lessons assigned for this most wonderful time of the year? Well, they are oddly foreboding, more threat than promise, more Apocalypse Now than It’s A Wonderful Life.

In this Advent series about “saints of the season,” the first saint we’ll talk about, Saint Nicholas, whose feast day is today, December 6, has a shadow side, too, just like Advent. He’s far edgier than the Santa Claus who came riding down 34th Street in his sleigh at the end of the Macy’s parade Thanksgiving morning. And I’ve come to the conclusion that dark and edgy are not such bad things…

When most of us hear the name “Saint Nicholas,” we think of the Christmas carol, “Jolly Old Saint Nicholas” or Clement Moore’s 1823 poem, A Visit from Saint Nicholas: “Twas the night before Christmas, …the stockings were hung by the chimney with care, in hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there…”

In his poem, Moore describes a miniature sleigh, eight tiny reindeer, and a little old driver, so lively and quick, who must be St. Nick… dressed all in fur, with twinkling eyes, merry dimples, cheeks like roses, nose like a cherry, a droll little mouth drawn up like a bow, the beard of his chin as white as the snow… and a little round belly that shook when he laughed like a bowlful of jelly. So Moore concludes he “had nothing to dread…”

Truth is, until very recently folks understood they very well may have something to dread when St. Nick came to town because you see, the St. Nicholas described in this beloved rhyme doesn’t bear even a remote resemblance to the real-life Saint Nicholas.

Nicholas was Greek, born to wealthy Christian parents in the seaport town of Patara in the year 270, about 235 years after Jesus of Nazareth died on the cross. Nicholas grew up to become the bishop of Myra (a Greek seaport city that was under the control of the Roman Empire—now part of Turkey). After his parents died, Nicholas distributed all of his sizeable inheritance to people living in poverty. When he was about 30 years old, he was imprisoned by the Emperor Diocletian and tortured as part of the last Roman persecution of Christians. When Constantine became Emperor in 306, persecutions ended, and Nicholas was released from prison. He served another 36 years as Bishop of Myra until his death in 342 CE.

Since his death, Nicholas has been named the patron saint of fourteen groups (including prostitutes, sailors, children, and brewers!), as well as eight cities, two countries (Greece and Russia) and one navy (Greek).

We know very little about Nicholas’ life, and only one other thing about his death: the poor old soul was not left to rest in peace. 700 years after he was buried in a tomb in Greece, Italian sailors raided the tomb and brought his bones to Italy. The fight over Nicholas’ bones continues to this day, with Turkey bringing a new lawsuit in 2009 to have them returned from Italy to Myra. In 2017, Pope Francis loaned one of Nicholas’ ribs to Russia, and over a million people lined up to see it in Moscow.

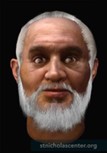

In recent years, forensic archaeologists have been allowed to examine his skeleton and use his skull to create a simulation of what “the real Santa” looked like (short and bald with dark brown skin, brown eyes, a short grey beard and a broken nose—likely received when he was imprisoned and tortured).

As I said, Old Saint Nick has not been allowed to rest in peace!

And that’s true in more ways than one. The few stories that were known about the historical man Nicholas, bishop of Myra, have taken on a life of their own—through misunderstandings, or the need to make him larger than life, or the impulse to tame his edgy side by turning him into a harmless Hallmark card Santa—his image has become blurred and obscured almost beyond recognition, especially here in America. (In many ways, we could say the same thing about Jesus—the man that baby asleep on the hay would grow up to become.)

One story about Nicholas that’s been tamed and softened over the centuries is the one about how he resurrected three children from the dead after they were murdered by a butcher who pickled their bodies in a barrel of brine in preparation for selling the meat as pork! Medieval artwork often shows Nicholas standing in front of a barrel that holds three naked babies. This is why he was made the patron saint of children and of brewers. But it seems that all people remember from this troubling tale is that St. Nicholas “loved children.”

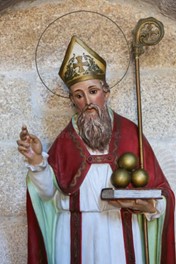

The most famous story told about Nicholas was how he saved three young women from becoming prostitutes (a music director at a church I once served joked that’s why Santa goes around saying “ho, ho, ho”). While serving as Bishop, Nicholas learned of a very poor family who couldn’t afford marriage dowries for their three daughters. Without money for the dowries, the only option left for the girls would be prostitution. Wanting to help, but also wanting to remain anonymous, Nicholas climbed up on the family’s roof in the middle of the night and dropped a bag of gold down the chimney, thus providing a dowry for the oldest daughter. The next night he did the same thing for the middle daughter. Because the girls hung their laundry by the fire to dry each night, the gold bags landed in their stockings. On the third night, the father of the family was determined to discover who was being so generous, so he waited outside and saw Nicholas drop a third bag of gold down the chimney. When he tried to thank the Bishop, Nicholas pleaded with him to keep his identity secret because he did not want to attract attention to himself, but eventually the story got out and is reflected in many paintings, tapestries and stained-glass portraits of Nicholas that show him holding three round bags of gold.

The edgier elements of this story have been erased over the years. No one talks about poverty or prostitution when they mention St. Nicholas today. We just have St. Nick “up on the rooftop,” secret gifts coming down the chimney, presents left in stockings “hung by the chimney with care.” And how many of you remember getting oranges in your Christmas stockings? That’s because in the Middle Ages, some people misunderstood the pictures they saw of Nicholas holding three round golden objects—thinking the objects were oranges, rather than bags of gold, they began to put oranges in children’s Christmas stockings as a sign that St. Nicholas had visited.

In Holland, this misunderstanding led to another: because oranges came from Spain, a legend developed that St. Nicholas (in Dutch, pronounced Sinterklaas, anglicized to “Santa Claus” here in America) lived in Spain and when he visited each December 6 (the feast day for St. Nicholas) he brought helpers with him who were “blackamoors,” enslaved black Africans who lived in Spain. Referred to as “Dark Pete,” these black men carried birch rods (or switches) that they used to beat naughty children (they left candy in the shoes of good children). They were also said to kick children who had misbehaved, or even to stuff them into St. Nicholas’ sack and take them back to Spain with them.

Other European countries have similar tales of these sinister companions to St. Nicholas: Krampus in Austria and Belsnickel (“Furry Nicholas”) in Germany, for example. (David Sedaris’ Christmas essay, “Six to Eight Black Men” is a hilarious take on this.) In America we have sanitized these figures and turned them into harmless, perky “elves” who work hard for Santa making toys and bringing Christmas joy.

After the Reformation, the veneration of saints was frowned upon in Protestant churches, so the big day for St. Nicholas to visit (and bring candy or terror) was moved from December 6 to December 25. Even the name and identity of the gift-giver was changed in some parts of Germany and Austria to Christkind (a.k.a. Kris Kringle), a golden-haired baby boy with wings symbolizing the newborn baby Jesus.

As European immigrants began arriving in North America, they brought many of these traditions with them, though in the Puritan colonies, celebrating Christmas was forbidden. It wasn’t until the 1800’s that Americans got into the business of reinventing Christmas into something that would look familiar to us today. Popular poems and songs helped to paint a portrait of St. Nicholas as a pipe-smoking Santa soaring over rooftops in a flying wagon, delivering presents to good girls and boys. They took the magical gift-bringing of St. Nicholas, stripped him of any religious significance except for the color red (the color of a bishop’s vestments), and dressed him in fur like the German Belsnickel. In 1822, when Clement Moore published that famous poem (“Twas the night before Christmas”) we get, for the first time, eight flying reindeer and a plump, jolly Santa. The visual transformation came thanks to the Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast, who, from 1863-1886, published a series of drawings of this Santa Claus, dressed in red long johns that were trimmed in white fur, living at the mysterious North Pole. (Nast chose the North Pole because of the popular expeditions there in the 1840’s and 1850’s that were unsuccessful in reaching the top of the world where it snowed year-round. No one knew who lived there, so why not Santa? Especially since, by this time, snow had become an important symbol of the Christmas season and reindeer were from Finland, a place of snow and ice.)

And so, the domestication of St. Nicholas, Bishop of Myra, was complete. Gone was a man who devoted his life to helping the poor, who worked to prevent the exploitation of women, who wasn’t afraid to look into the bleakest corners of his world where children were murdered. Gone was a man of faith so deep and brave that he endured imprisonment and torture rather than betray his God. This man, who wanted nothing more than to remain completely anonymous as he went about doing good for the oppressed, has been replaced with a cartoon character splashed across billboards for Coca-Cola, sitting on thrones in shopping malls, and starring in prime-time TV shows.

We look at the Saint Nicholas of today, and with a wink of his eye and a twist of his head he soon gives us to know we have nothing to dread—and that’s just how we like it. In the same way, our celebration of Advent is too often reduced to opening a door each day on a cute paper calendar and finding a sweet treat. But Jesus doesn’t let us off the hook that easily, “But about that day and hour of the coming of the Son of Man, no one knows. It will be like the days of Noah were, when they knew nothing of the coming flood until it came and swept them all away. Keep awake therefore, for the Son of Man is coming at an unexpected hour.”

It’s so tempting to clean up and sweeten stories about difficult things like poverty, exploitation, torture or about the apocalyptic coming to earth of the Son of Man, Emmanuel, God with us. But the gospel urges us not to give in to that temptation. To be courageous enough to tell the truth, to confront even those things that disturb us. After all, “apocalypse” is a Greek word that means, literally, to uncover, disclose and reveal that which is covered, protected and concealed.

So much is lost when we forget the dark and edgy parts of any story, whether it’s about Saint Nicholas, or about the birth of the Christ Child at an unexpected hour in a dark and unexpected place. In the weeks ahead, let’s not forget that Advent has a dark side and let’s resist the temptation to clean it up or sugar coat it. Let’s allow it to make us squirm a bit and acknowledge that we have gotten too comfortable with both a faith and a God that are rather ‘safe.’

In C.S. Lewis’ gospel allegory The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, a young girl asks if Aslan, the great lion ruler of Narnia and Christ figure, is “safe.” “’Course he isn’t safe,” she is told, “But he’s good. He’s the King.” Thanks be to God.