Lent begins today

Photos from “Unto Dust” by Greg Miller

Lent begins today, Ash Wednesday, with a ritual designed to remind us of our mortality. “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”

As a child growing up old-school Presbyterian, I never went to an Ash Wednesday service or received a black cross of ashes imposed upon my forehead. That was something the Catholic kids who went to catechism at Our Lady of Good Counsel did. So, when I was 26 years old and serving a church that combined a Presbyterian and an Episcopalian congregation (Episcopalians do practice imposition of ashes), I was on a steep learning curve that first Ash Wednesday. The Senior Pastor put me in charge of leading the small evening service, so before heading off to church that morning, I scooped some ashes out of my fireplace grate into a plastic zip-lock bag and brought it to church.

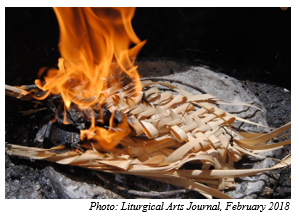

“WHAT is that?” asked the Episcopal rector. From the look on his face, you would have thought I was placing a dirty diaper on the altar. When I explained they were ashes from my fireplace, I believe he may have suffered a small aneurysm—I’m not sure. But he recovered quickly and explained to me (as if he were speaking to a rather dimwitted child) that ashes for Ash Wednesday were created by burning the blessed palms from last year’s Palm Sunday service. He said his altar guild had plenty and he’d give me some. He told me to burn them outside, and then he said something about olive oil.

Silly me. I thought the olive oil was supposed to work like lighter fluid, so I put the crunchy, dried palm fronds into a metal salad bowl, splashed them with lots of oil (like dressing a salad, really) and carried it all outside where I threw a lit match into it and stepped back. Nothing much happened at first. I finally managed to get them to burn, but I ended up with about a teaspoonful of gloppy, oily black sludge in the bottom of a scorched bowl. (Turns out the oil was supposed to be dripped into the ashes after the palms were burned—who knew?!) I carried the mess back inside, at which point the exasperated Rector went to his sacristy, got a pyx (great Scrabble or crossword puzzle word!), filled it with some of the ashes he had made and handed it to me with a look of pity mixed with disgust.

As embarrassing as my liturgical ignorance was, I still think I did better than a seminary classmate of mine who realized with just five minutes to go before his first Ash Wednesday service that he had no ashes, so he went to the copy machine (oh yes, he did), scooped some black toner ink into a bowl and used that to anoint his parishioners. Let’s just say, it did not go well.

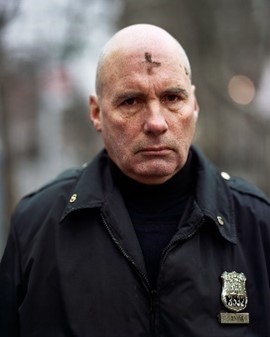

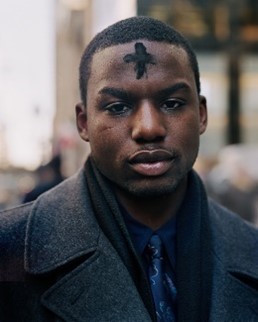

It’s an odd thing we do, isn’t it, on the first day of Lent every year? 46 days before Easter, on a Wednesday, we smudge black ashes in the shape of a cross on our foreheads and hear the words, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

Why ashes?

Lent is a season of penitence and introspection, and since the bible tells of using ashes as a sign of repentance and sorrow, it makes some sense that we would mark our foreheads with ashes on the first day of a penitential and introspective season.

Ashes also serve as a reminder of our mortality—ashes to ashes, dust to dust, as the funeral liturgy goes—and a reminder of our humanity, that we are creatures created by God from dust.

The words can be heard a number of different ways: as a threat—clean up your act before it’s too late; as a wake-up call—none of us gets out of here alive, so make the most of every single moment and don’t take life for granted; as a reminder—you are not God, you are created by God from dust so know your place. The word “humility” comes from humus, the Latin word for earth. The ashes are symbols of the earth, and a reminder that we are all creatures of the earth.

Ashes are a reminder that our lives are short and so we must live them to the fullest, not taking one second or one person for granted, and appreciating each second and each person with wonder, praise and joy at the beauty of this uncertain and transitory life.

When I experience the very real discomfort of seeing such a visible reminder of my own mortality staring back at me in the mirror on Ash Wednesday, I see the shape the ashes take—the cross—as a reminder of an even more powerful truth: that love is stronger than death. And I share the poet, Jan Richardson’s, perspective on what the ashes represent: because they are the ashes of those palm branches that just nine months ago were alive and green, “deep within the ashes’ darkness and dust lies the imprint of green, the memory of life, the awareness of what has gone before and of what may yet be.”

After all, ashes make excellent fertilizer, providing lime, potassium and trace elements that new plants need to thrive. And ashes are used to make soap, which means they hold the power to wash away all manner of sin and guilt, leaving us with a clean, fresh start.

For me, this is all living proof of the gospel’s good news that there is more grace in God than there is sin in us.

God does amazing things with dust and ashes. God brings hope out of despair, joy out of sorrow, life out of death. This season of Lent calls us to open ourselves to the God who brings life from ashes, who works wonders amid destruction.