Saints of the Season

Advent 3 – Saint Lucia

A reflection by Executive Director Rev. Jane Field

When I first began working as the Executive Director of MCC, I also accepted a call to serve as the pastor of a Lutheran Church. As an ordained Presbyterian minister, I imagined how lovely it was going be to celebrate Advent “the Lutheran way,” with a bunch of Swedes, Norwegians and Danes and a beautiful blonde girl wearing a gossamer white nightgown and red sash processing around the sanctuary with a wreath of candles on her head. I just assumed that’s what all Lutherans do on December 13, the feast day of Sankta Lucia.

As my first Advent with the Lutherans approached, I began asking pillars of the church what their traditions were for celebrating St. Lucia Day. I got some puzzled looks, and a few “What’s that?’s” But those who knew what I was talking about, simply told me with a nonchalant shrug, “We’ve never done that here.” There weren’t going to be any gossamer-gowned girls wearing crowns of candles. [Failure trombone!]

That wasn’t the only surprise I got that Advent. In preparing a sermon for the Sunday closest to Saint Lucia’s feast day, I read up on the blonde-haired, candle-wearing saint and learned she wasn’t Scandinavian at all! In fact, she was from the Italian island of Sicily from a town called Syracuse. And she wasn’t originally called Sankta Lucia (“loo-see-ah”), but Santa Lucia (“loo-chee-ah”).

“Loo-chee-ah” (Lucia) was born in Sicily near the end of the 3rd century, about 250 years after Jesus of Nazareth was crucified. Her family was very wealthy; her father, of Roman origin, died when she was only five years old; her mother, Eutychia, was of Greek origin. We don’t know whether Lucia’s parents were Christian or not, but we do know that by the time she was a teenager, Lucia definitely was. This became a problem when her mother arranged a marriage for her with a wealthy Roman who was not a Christian.

When this wealthy young Roman pagan learned that his bride-to-be was a Christian, he was pretty upset. He got even angrier when he found out that she was regularly bringing food and water to the Christians hiding in the catacombs. She did so wearing a wreath of candles on her head to light the way into those dark tunnels. (Wearing candles on her head freed up both her hands so she could carry even more food with each trip.) Then, when her fiancé discovered that Lucia had been following Christ’s command to give all that she had to the poor by giving away her inheritance, including her dowry, well, that was the last straw! Her fiancé broke off the engagement and reported her to the authorities.

Being a Christian or aiding and abetting Christians was against Roman law at that time. The Emperor Diocletian had instituted a brutal crackdown on Christianity, persecuting any believers who would not renounce their faith and worship the emperor instead. Christians were tortured, enslaved, stoned to death, beheaded, burned at the stake, or fed to wild animals as a form of public entertainment.

Lucia was arrested and imprisoned after her (former) fiancé turned her in. The Roman authorities sentenced her to work in a brothel when she refused to renounce her faith, but legend has it that when the guards came to take her away, they could not move her, not even with the help of oxen brought to drag her out. So the decision was made to burn her at the stake, using her bible as kindling for the fire around her feet. But no matter how many times they tried, they could not get the fire to light. Throughout this entire ordeal, Lucia is reported to have been preaching the gospel and predicting that her captors would soon be overthrown. Finally, one of the guards took a long dagger and drove it into her throat to silence and kill her. Some later accounts, not popular until the 15th century, claim that her tormentors also gouged her eyes out, and that when her family prepared her body for burial, they discovered her eyes had been miraculously restored. (Which is why Saint Lucia is the patron saint of eyesight.)

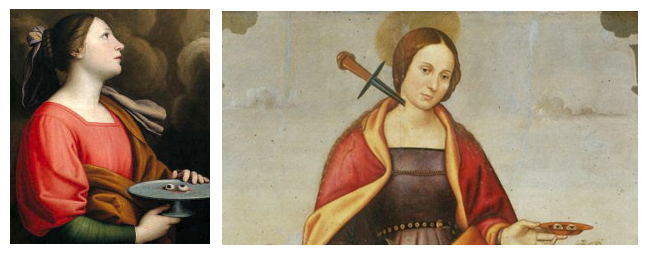

This rather gruesome demise is depicted in statues, icons, stained glass windows and paintings all over Europe. Frequently, Lucia is shown daintily holding a plate with two eyes on it! And then there are the statues of a beautiful, young, graceful woman dressed in flowing robes…with a dagger stuck into her throat! Just plain weird!

Anyone who was martyred for their faith during the earliest centuries of Christianity was automatically considered a “saint.” And by the 6th century, Saint Lucia had become well-known throughout the church, as had the many stories and legends about her. And, just like St. Nicholas and St. John the Baptist, as had her bones! It seems her tomb lay undisturbed for about 400 years, but after that, her bones were moved again and again—all over Italy, then to Constantinople, Germany, back to Italy—from Venice to Rome to Naples to Verona to Milan and back to Venice where, in November of 1981, thieves stole all her bones except for her skull. (The bones were returned five weeks later on her feast day.)

It wasn’t just her skeleton that took a road trip. During the Middle Ages, Christian missionaries came north into Scandanavia, telling stories of Saint Lucia, the young girl who brought light in the midst of darkness, whose very name means “light” and whose feast day just happened to fall on the longest night of the year—the winter solstice (the Julian calendar was still in use at that time, so December 13 was the solstice). No doubt, the story of Sankta Lucia (“loo-see-ah”) held great meaning for these people of the north living on the edge of darkness in frozen December when the night could last as long as 21 hours. Surely they were longing for warmth and light.

In fact, long before Christianity reached that part of the world, Scandinavian people mounted candles on evergreen wreaths or wooden wheels during the cold winter months to implore their gods to turn the dark season back to a time of warmth and light. As these northern Europeans became Christians, many of these old traditions that centered on the annual struggle between light and darkness took on new meanings. Against the harsh landscape of their dark winter, Lucia symbolized to these Scandinavians hope and the return of light to the world. The words of Matthew 4 must have had special meaning for them at this time of year: “the people who sat in darkness have seen a great light, and for those who sat in the region and shadow of death, light has dawned.”

Despite the ancient roots, modern-day St. Lucia traditions only emerged in the past one to two hundred years. The first recorded appearance in Sweden of a girl dressed as Lucia in a white gown with a wreath of candles on her head was in a country house in 1764, though the custom did not become universally popular in Swedish society until about a hundred years after that. The custom of girls dressed as Lucia serving their parents coffee, ginger cookies and saffron buns dates back to the 1880’s.

Nowadays, in Sweden, Norway and parts of Denmark, on the morning of St. Lucia’s Feast Day, the eldest daughters in households dress in white robes (symbolizing the baptismal gown and purity) with red sashes (symbolizing martyr’s blood) and with wreaths of lighted candles on their heads, carry a breakfast of coffee, ginger cookies (symbolizing warmth) and bright yellow saffron buns (symbolizing the sun), to their parents’ bedrooms. The younger daughters of the household follow them carrying a single candle. Their brothers, called “star boys,” wear tall, pointed caps or dress as gingerbread men. Later in the day, a Lucia procession may go to hospitals and nursing homes to sing for the patients, and many Lutheran churches will incorporate a Lucia procession into a special evening liturgy that night, or on the Sunday closest to December 13. Since 1927, it’s been common for each town and village to crown a “Lucia” every year, and until recently a national “Lucia” was crowned (like Miss America).

Interestingly, the Danish were late to the St. Lucia game—adopting the custom from Sweden in 1944, at the height of World War II. A Secretary in the Danish Foreign Office imported the idea as an attempt to, as he put it, “bring light in a time of darkness.” It was meant as a peaceful protest and passive resistance to the German occupation of Denmark, but has been a tradition there ever since.

An important part of the Lucia procession is the song the girls sing as they walk. Originally an Italian folk song about the beautiful views from the port city of St. Lucia (actually still sung by gondoliers in Venice), the Swedish words are about light breaking into the long darkness of winter.

Below, you’ll find a link to a recording of a traditional Swedish Saint Lucia procession, but first read this translation of the words the girls will be singing and reflect on how, during Advent, we, too, celebrate the light breaking forth in darkness—with the lights on our Christmas trees, with the candles on our Advent wreath, and with the single, small candle each of us will hold on Christmas Eve as we sing “Silent Night.” All of these traditions point us toward remembering the birth of the Prince of Peace and the light he brings into the world. “What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.” (John 1:3b-5)

During this holy season of Advent, may each of us, like Lucia once did, find ways to bring light and life to the persecuted and outcast in the midst of this world’s longest, darkest nights.

Receive these words as an Advent prayer:

Night walks with a heavy step round yard and hearth.

As the sun departs from earth, shadows are brooding.

There in our dark house, walking with lit candles,

Sankta Lucia, Sankta Lucia!

Night walks grand, yet silent, now hear its gentle wings,

In every room so hushed, whispering like wings.

Look! At our threshold stands, white-clad with light in her hair,

Sankta Lucia, Sankta Lucia!

Darkness shall take flight soon, from earth’s valleys,

So she speaks wonderful words to us:

A new day will rise again from the rosy sky…

Sankta Lucia, Sankta Lucia!Click HERE to watch as this is sung in Swedish as part of a traditional Sankta Lucia procession