Putting Some Meat on the Bones of God’s Air Raid Siren

Saints of the Season – John the Baptist

The musical “Godspell” begins with John the Baptist interrupting philosophers debating the meaning of life. John blows loudly on a shofar (ram’s horn) and then sings ten simple, clear notes: “Prepare ye the way of the Lord.” His voice cuts through the chatter of the philosophers and they fall silent. Then they begin singing along, change into clown costumes, and ask John to baptize them.

That’s how John The Baptist got his last name, after all, by baptizing people—it wasn’t because he went to a Baptist church! He even baptized Jesus.

John the Baptist was out there in the wilderness on the banks of the Jordan River baptizing people because he believed God had called him to be a prophet who prepared the way of the Lord. In the decades after his death, the earliest Christians began to call him a “saint,” and he is still venerated in Western and Eastern Christianity today. This Advent, we’re continuing our series on “The Saints of the Season” by taking a look at Saint John the Baptist.

We don’t know a whole lot about him. He’s mentioned in all four gospels—though some provide more details than others—and he appears outside of the bible in the Roman historian Josephus’ writings. (BTW: John the Baptist is NOT the “author” of the gospel of John, nor is he the “John” of the twelve disciples.) While Luke’s gospel fills in background details about John the Baptist (his mother and father were Elizabeth and Zechariah, he was a relative of Jesus, he began his ministry in the 15th year of the reign of Roman Emperor Tiberius Caesar—around 26 CE), Matthew’s gospel says only that John “appeared” in the wilderness of Judea preaching to crowds of Jews who gathered there, demanding that they “Repent! For the kingdom of heaven has come near!”

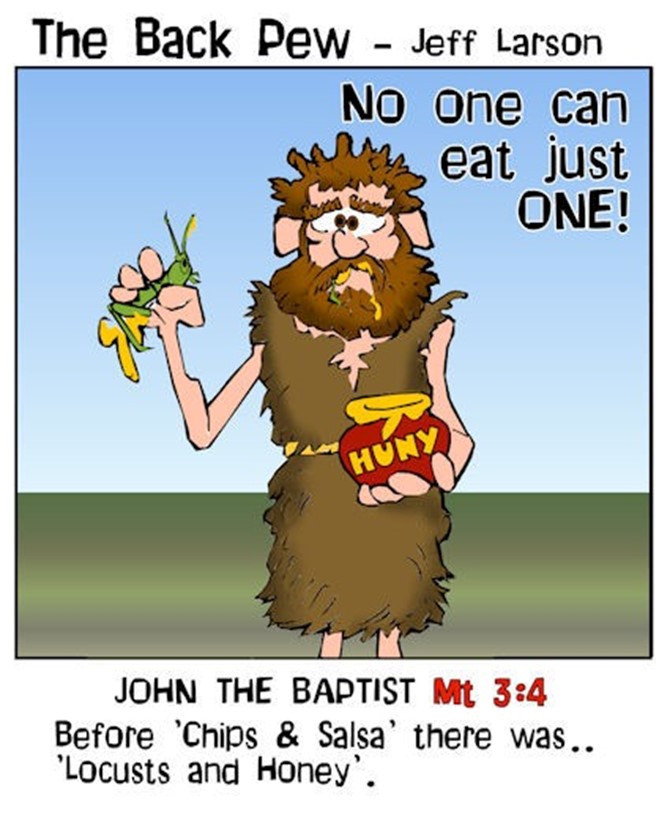

Even though Matthew doesn’t seem to have much information about where John came from, he does have some very detailed information about what he wore, what he ate and where he chose to live! In fact, all three of the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) make a point of describing John’s peculiar fashion statement: he wore clothing made of camel’s hair and a leather belt. This must have made quite an impression — none of the gospels describe in that much detail what Jesus himself wore!

John’s culinary preferences were also remarkable, according to the gospel writers: he ate locusts (as in bugs!) and honey. And he lived way out in the wilderness, about 18 miles from Jerusalem, a long day’s journey on foot. It seems like maybe the gospel authors were trying to find a polite way of saying, “This was one weird guy.”

Maybe. But they were also signaling to their listeners with cues that are easy for you and me to miss or misunderstand. You see, there was a Hebrew prophet who lived about 800 years before John the Baptist who had the same taste in clothes, food and neighborhood: Elijah, who’s described in 2 Kings as “a hairy man with a leather belt around his waist.” Elijah spent time in the wilderness, eating only what the ravens brought him, and he is said to have departed the earth in a chariot of fire that came for him at the exact same spot on the Jordan River where, 800 years later, John was doing his baptizing. (It’s also the same spot on the Jordan River where Joshua led the Israelites into the Promised Land after their 40 years wandering in the wilderness.)

These cues would have pointed Jews and then the earliest Christians to recognize John the Baptist as a prophet in the grand old tradition of Hebrew prophets. This was significant, in part, because when John the Baptist came along, it had been 450 years since Israel had heard from any prophet at all. He was the first one in 450 years!

So, if he understood his job as being the prophet who prepared a way for the Lord by calling the people of Israel to repent and warning them that the kingdom of heaven was near, why was he spending his time taking people out into the middle of a river and holding them underwater? Did he invent baptism—is that how he got “Baptist” for a last name? Actually, no. Baptism and ritual cleansing was being done by many different groups within Judaism at that time.

Wherever he got the idea, John thought baptizing was essential because he believed his people—the people of Israel—had lost their way, become corrupted by greed and power, and failed to follow God’s law. He wanted them to be baptized as a sign that they repented from these terrible mistakes. That way, they would be purified, ready, and right with God when the kingdom of heaven arrived—something he was convinced was about to happen any minute. The urgency he felt about this meant his preaching was all fire and brimstone all the time (Barbara Brown Taylor refers to John as “God’s own air raid siren” and “the Doberman Pinscher of the gospels”!!).

He must have been good at what he did, because he was attracting lots of followers who were making the 18-mile trek out to the boondocks to hear his message and be baptized by him. This made the Roman occupiers very nervous, which would eventually spell big trouble for John.

Long before that happened, though, Jesus of Nazareth made his way out to the wilderness where John was preaching and baptizing. Some scholars think Jesus spent a long time there (maybe even a couple of years) and was actually one of John’s followers before he began his own ministry. In fact, they think the gospel writers had a little problem to overcome: John the Baptist was so popular that he continued to have loyal followers even after Jesus began his ministry, and John himself never became a disciple of Jesus. And because John baptized Jesus (and not the other way around), the gospel writers had to bend over backwards to try to show that John was not “superior” to Jesus and didn’t have authority over Jesus. There was likely a little power struggle going on between the followers of John and the followers of Jesus.

But if there was, it didn’t last very long. Because those nervous Roman occupiers I mentioned? They finally had enough of John’s shenanigans in the wilderness, and, fearing he would soon incite a rebellion among the Jews against Rome, went ahead and arrested him and had him executed by beheading. (Which is how he became one of the earliest to be called a “saint”—because he was martyred for his faith.) Once John was dead and gone, his followers, for the most part, shifted their allegiance to Jesus and the two groups became one. And it was only then that Jesus’s own ministry really took off

By about 30 CE, John the Baptist was dead and gone, but like Saint Nicholas from last week, he was not allowed to rest in peace. Once again, we have a story of a saintly skeleton going rogue, refusing to stay dead and buried in one place. In 2010, during an archaeological excavation of a 5th century Bulgarian church (on Sveti Ivan island—translation: Saint John island), a small box carved from marble was found under the altar. Inside? Six human bones—a knucklebone from the right hand, a tooth, part of a cranium, a rib, and an ulna, or forearm bone. Next to the marble box, the archaeologists found a smaller box made of hardened volcanic ash that was inscribed in ancient Greek with John’s name and birthdate.

Much to the surprise of scientists, DNA and radiocarbon testing of the knucklebone revealed that the human remains belonged to a Middle Eastern man from the 1st century (not a European man from the 5th century, as they had expected). While it can never be proven one way or the other that the bones are really John’s, the test results do show the bones are the right age and come from the right geographic area to have been John the Baptist’s. Archaeologists theorize that the smaller box was the original container used to transport the bones from the Middle East to the island, where the marble casket was then constructed to house the bones under the church altar. The bones are now on display in Sofia, Bulgaria. Sadly, the rib was recently stolen, so John is on the move again!

These stories about Saint Nicholas’ and Saint John the Baptist’s bones are like a metaphor for what we can know about our forerunners in the faith, about this communion of saints. Hundreds or even two thousand years after they walked this earth, we’re left with just a part of their body—and a part of their story.

The Lord set me down in the middle of a valley; it was full of bones. He led me all around them; there were very many lying in the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, “Mortal, can these bones live?” I answered, “O Lord God, you know.” Then he said to me, “Prophesy to these bones, and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. …So I prophesied as I had been commanded; and as I prophesied, suddenly there was a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone. I looked, and there were sinews on them, and flesh had come upon them…

(Ezekiel 37:1-8)

Can these bones of our saints live? Can God make their dry bones dance? Yes. Because, with God’s help, we can knit these saints back together; through stories and imagination and scholarship we can put flesh back on their bones.

Even if the bones in Bulgaria weren’t John’s, but some other nameless 1st century Middle Eastern man’s, it doesn’t really matter, because the fact remains, somewhere there is a bone that was in a hand that touched Jesus.

Putting flesh on bones—that’s what incarnation is—literally, enfleshing (Latin carne, like “chili con carne” (with meat) or carnivore (flesh eater)). That’s what we do when we bring these saints back to life through our stories, we flesh them out, incarnate them, put some meat on their bones.

More importantly, it is what God did when the baby whose arrival we await this Advent season was born and laid in a manger in Bethlehem. And that good news is enough to make even our dry old bones dance!