The Other Good Samaritan

Third Sunday of Lent

The conversation Jesus of Nazareth has with the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4:5-42) is the longest dialogue he has with anyone in any of the gospels—longer than those he has with his disciples, or with his accusers, or even with his own family members.

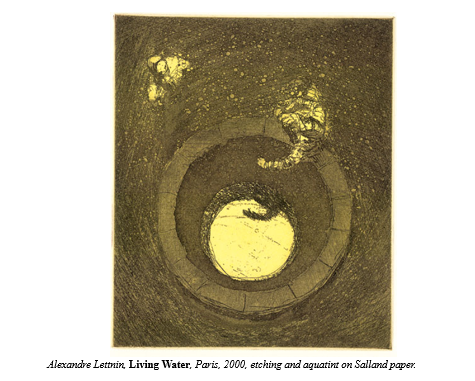

The assigned text for the third Sunday of Lent this year, the story of this conversation is depicted in Brazilian artist Alexandre Lettnin’s etching, Living Water, shown above. Painted when Lettnin was living in Europe and feeling lonely as an outsider, a foreigner, his engraving offers a “God’s eye view” of the well, just as Jesus’ acceptance of the Samaritan woman gives us a God’s eye view of marginalized people who are seen as outsiders.

In first-century Palestine, the Jewish people of Judea (Jesus’ people) detested Samaritans. Because Samaritans were the descendants of Israelites who had inter-married with their Assyrian conquerors, Jews considered them and their land to be unclean and impure. If a Jewish person came into contact with a Samaritan, or drank from the same cup, for example, an extensive ritual cleansing would be required. (You may remember that this is why Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan was so shocking to his followers.)

There were also strict rules governing gender roles. It was considered highly improper for men to speak with women in public. It would have been morally problematic that the Samaritan woman in this story was now living with a man who is not her husband—which may be the reason she comes to the village well at noon. (The other women of the village would have come to the well in the cool of the early morning to collect water and to socialize. Perhaps the woman from our story was not welcome in those circles because of her living arrangement.) She was an outsider even in her own village.

Her outsider status is central to the story. This woman is an outsider three times over—an outsider to her culture, because she is a woman; an outsider to Jews because she is a Samaritan; and an outsider to her neighbors because she is a woman living with a man who is not her husband.

It is into that complicated reality that Jesus walks and asks her for a drink of water. He should not be talking to her at all. But he does. He should not be willing to drink from her water jar or come into contact with her. But he is. He crosses deeply ingrained social boundaries and seems unconcerned at the prospect of putting a “polluted” Samaritan drinking vessel to his lips, or of settling in for a long, public conversation with this woman.

This story sets the stage for the rest of Jesus’ ministry—laying it out right at the beginning, “Reader, beware! Jesus had a distinct fondness for overstepping society’s boundaries, and his ministry addressed and included those who were considered ‘outsiders.’” In this case, when he meets a woman who couldn’t be more of an outsider, he receives her as an insider—even referring to her with the same term he used for addressing his own mother (“Woman”). He receives the Samaritan woman at the well with respect, grace and love. And rather than getting up and leaving as societal norms dictated she should, she stays, showing her own courageous willingness to break taboos.

At the end of their conversation, Jesus reveals to her who he really is—after she mentions that she knows that when the Messiah comes, he will know the answers to her questions about God, Jesus says, “I AM. The one who is speaking to you.” The divine name, as revealed to Moses in the burning bush, “I AM,” is how Jesus reveals to this three-strikes-you’re-out outsider that he is the Messiah and the incarnation of God. It’s the very first time he reveals his true identity to another living soul—and it’s to this outsider, this Samaritan woman who is shunned even by her own village.

One of the most important truths revealed about Jesus in this story of the Samaritan woman at the well is that he chooses the outsider, the outcast, the one living on the fringe of society, to honor, to affirm, to respect, no matter what boundaries he has to step over to do so, and it is through these outsiders and outcasts that he is most likely to reveal himself to the rest of the world. Because of Jesus’ clear and consistent preference for the outcast, the outsider, the lost and the lonely, when we want to look for him, we should look for and listen to them.

This Lent, may each of us, may all of us, learn to listen to the outcasts, misfits and outsiders who can help us find our way to that well of living water where we can encounter Jesus, too, tell him the truth of our lives, and learn the truth of his life, death and resurrection, even as we embrace its mystery.