“Dead Man Walking”

Lent 5

One day, more than twenty years ago, as I picked up my daughter from preschool, I could see the head teacher, Joey, standing outside the playground gate with a clipboard, grimly speaking with parents. “Hi Jane,” she said as she checked my name off her list. “We are letting parents know that we had an …incident at school today. Several of the children were very upset, and it may come up at home tonight, so we wanted you to be prepared.” Usually bubbly and cheery, Joey looked as if she was about to burst into tears. “What happened?” I asked.

“This morning, during chore time, the student who was responsible for feeding the gerbils noticed that Whitey [I kid you not, so help me God, the classroom gerbils were named Whitey and Blackie!] …the child noticed that Whitey wasn’t moving around in his cage. In fact, Whitey wasn’t moving at all. So, we teachers thought it was important to talk to the children during morning circle time about Whitey’s …passing.” And that’s when, as I could tell from Joey’s expression, things had gone terribly, terribly wrong. (Although, I suppose from Whitey’s point of view, things went wrong somewhat earlier.)

Joey explained that the teachers asked the children if they had any questions. One child asked, “Why did Whitey die? We only had him for a couple of years.” In trying to explain death to this group of preschoolers, one teacher offered this helpful explanation: “Little things have short lives and big things have long lives.” The circle of panic-stricken children looked at each other in horror, at their own little bodies and their own small faces and their own tiny hands…one child began to wail. Little things have short lives?!?

Now another brave teacher waded in as a different child cried out, “But how old was Whitey?” “Oh, he was about 3 or 4 years old.” Remember, this was a preschool classroom. Full of children. Who were all 3 or 4 years old. Two more of whom now began to weep in terror. Why hasn’t anyone told us this awful truth before??? We’re all gonna die!

That afternoon, as she gripped her clipboard at the playground gate, Joey assured me in a tone used by funeral home directors, that the teachers did eventually manage to calm the children down. Out of sympathy for poor Joey, who clearly did not see any humor in this situation whatsoever, I managed to keep a straight face as I walked through the gate, thanking her for letting me know about “The Unfortunate Incident.”

When my daughter and I trooped inside to collect her lunch pail and sweater, I was relieved to see that she didn’t seem the least bit upset. Before we left, she went out into the hallway to get a drink from the water fountain.

The end-of-day routine for teachers at this preschool included bagging up the classroom garbage and leaving it in the hallway for the custodian to dispose of. [You see where this is going, don’t you?] As I walked into the hallway, I could see my little girl calmly standing near one of the clear trash bags, quietly bent over at the waist with her little hands folded behind her back and her head cocked to one side. She pointed to something inside the bag and said, “Look, mom, there’s Whitey!”

Yes, it’s true. Lying serenely among the construction paper scraps, discarded lunch bags and empty glue bottles was the stiff, still, furry little body of Whitey, awaiting its final dispatch to the big green dumpster in the parking lot.

Those poor, poor teachers! Theirs was a difficult task, and they did try, God bless them, to handle Whitey’s death as best they could. (Though why someone thought using a clear plastic garbage bag on that particular day was a good idea? I’m just saying!) But otherwise, faced with a daunting challenge, they tried to rise to the occasion and speak honestly when death paid a visit to their classroom.

Who among us finds it an easy thing to contemplate death or talk about it plainly? Think of the euphemisms we use: we put our pets “to sleep,” we say that Uncle Edgar “passed away,” we explain that Great Grandma “went on to her great reward.” We refer to dead relatives as “the dearly departed” who “rest in peace” or we joke that old so-and-so “bought the farm,” “kicked the bucket,” or “met his maker.” Let’s face it: we are pretty uncomfortable thinking about, talking about, dealing with death.

I’ve heard some say that Christians are guilty of turning death into a minor matter, a simple freeing of the soul from the prison of the body, a quick transition to blissful immortality, that Easter gives us some kind of cosmic “get out of jail free” card that removes the sting of death for true believers. Nothing could be further from the truth.

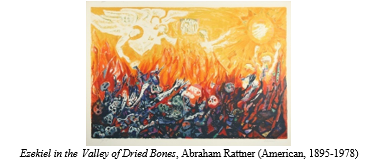

The Bible, and in particular, the scripture lessons we heard this fifth Sunday of Lent (Ezekiel 37 and John 11), make no bones (excuse the pun) about the seriousness of death. In these two stories (Ezekiel’s valley of dry bones and the raising of Lazarus), death is final and impossible for humans to undo. And according to both Ezekiel and John, death causes anguish, despair and sorrow for those who mourn.

Christians also have the season of Lent that begins with Ash Wednesday, when, with the mark of ashes pressed onto our skin, we are reminded we will return to the ground, for out of it we were taken. During the forty days of Lent, we journey with Jesus to Jerusalem and on to Golgotha (literally, “the place of the skull”), a place littered with the bones and corpses of all those crucified by the Roman empire. There, on Good Friday, we stand to watch Jesus die on a cross. To me, that does NOT sound like a faith that tries to dodge death or deny its power.

Yes, we have Easter, too, with its trumpets and lilies and an empty tomb victory over death, but it is not Easter yet. It’s getting closer, true, but, as Barbara Brown Taylor says, “we have to walk through a graveyard to get there.”

Maybe that is why, on the 5th Sunday of Lent, we are given the stories of dry bones coming to life with the breath of God, and of Jesus raising Lazarus from his stench-filled tomb. These stories are meant to reassure us, as we prepare for our walk through the graveyard, that “there is a power loose in the universe that is stronger than death, stronger even than our fear of death.” (B.B. Taylor)

Neither of the stories tries to say that death doesn’t matter, or isn’t important, or shouldn’t upset us. Quite the contrary. Each story marches straight ahead—into a valley filled with dry bones as far as the eye can see, into the midst of a grieving family standing at their brother’s tomb where his decomposing body has lain for four days. Once there, each story raises a question: “Mortal, can these bones live?” God asks Ezekiel. A weeping Jesus asks Martha, “Do you believe that I am the resurrection and the life?”

The answer to those questions is that, despite how vast the horrible valley full of bones was, or how final the tomb’s dank stench, God gets to have the last Word, and death does not. In the answer, God reveals the divine purpose to save and to fashion a new people out of dead bones, to bring life out of death, to affirm love in the midst of loss, hope in the midst of despair, and to overcome the thing that overcomes us all. God is in the business of calling forth light and life where we see only darkness and death. Even more amazing, God accomplishes this not by going around death, but by going right through it.

However, the raising up of dry bones and of Lazarus are not just a preview of “coming attractions” because there are continual miraculous raisings and renewals that happen throughout our lives, transforming us again and again as we experience all the smaller deaths life deals out along the way. God stands at the mouth of every tomb we find ourselves in, not just the tomb into which we’re laid at the end of our physical life—tombs of despair or denial; tombs we find ourselves in after we’ve died to an old way of living but wonder if we will really ever live again—after a divorce, a job loss, your last child growing up and leaving home, a retirement, being forced to move from a home you loved, the aftermath and devastation of a natural disaster or a war, the death of someone you love. In the midst of such loss, living can feel more like dying. Like Ezekiel’s Israel, living in exile, we say, “Our bodies are dried up, our hope is lost, we feel cut off completely.” Lazarus-like, we find ourselves trapped in a tomb.

It is then that God arrives, weeps for the pain and the loss we have suffered, and then yells into that tomb of ours, “Come out! Come out so that you might truly live!” And with the Spirit of God breathing new life into our dry bones and bandaged limbs, just as it blew life into the very first human beings when from dust and ashes they were created, love unbinds us, sets us free, and we rise. We rise.

Maybe each year on Ash Wednesday, with its talk of our returning to dust and ashes, and on Sundays in Lent (especially the fifth Sunday, with its stories of dry bones and dead friends), and on Good Friday, as Jesus hangs on a cross and dies, churches should post a “Joey” outside their sanctuary doors, clipboard in hand, ready to greet each new arrival with a grim warning about what is going on inside. After all, we are talking about death. But this is not preschool. It is church. And while poor old Whitey’s body ended up in a plastic garbage bag, we gather in church every Sunday to remember and celebrate that Jesus’ tomb was empty, there was no body. And that is why death is not the last word spoken here.

Thanks be to God.